There are a lot of things I can choose to focus on for this series, but I have settled on one broader theme: "Catch-22s in First Nations Depictions" refers to the times and contexts in which simplistic means of interacting with the First Nations peoples and their cultures simply fall apart. They are about the stereotypes and common images that have become predominant in how Canadians have come to perceive our First Nations - some more successfully and appropriately so than others.

Before I begin, a quick disclaimer: I, Kita Inoru, am NOT a person of First Nations descent. What this means is that the perspective and the opinions that I express here are solely my own. If there is anyone here who is of First Nations descent and/or is directly affected by the issues discussed in this series, please feel free to shed further light on them in the Comments, and please be patient with me in regards to any errors I might make. Thanks!

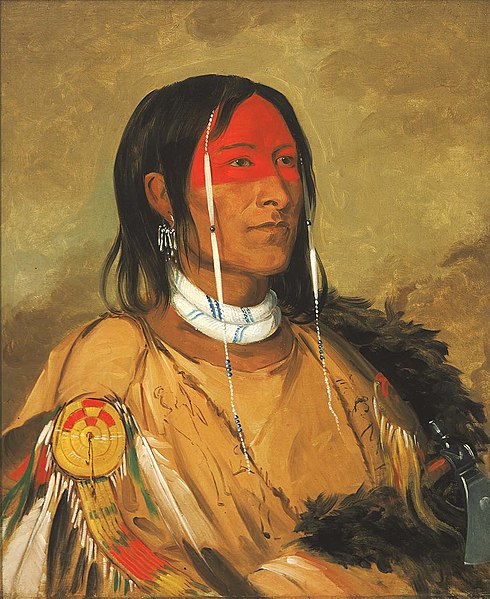

My discussion, then, begins with what is probably among the oldest and most iconic images that we have of the First Nations peoples in Canada: the Noble Savage.

|

| "Eeh-tow-wées-ka-zeet, He Who Has Eyes Behind Him (also known as Broken Arm), a Foremost Brave" by George Catlin (1832) |

For the most part, the Noble Savage is simply that: a "Savage" who exhibits "Noble" characteristics. However, I find that that does not show the sheer complexity in terms of how the First Nations have been perceived either historically or in the present day. The way, then, that I would like to examine this concept is to break it down into two main groups of characteristics: those that are "Noble", and those that are "Savage".

|

| Detail showing an Iroquoian warrior in "The Death of General Wolfe" by Benjamin West (1770). This is now one of the most iconic representations of the Noble Savage in 18th century artwork. |

Conversely, and concurrently, there is the image of the "Savage". This is the concept of the First Nations as hardened warriors who raid European settlements, scalping, enslaving, and killing the inhabitants. It is the image that looms large in the French Jesuits missionaries' descriptions of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) in their wars with the neighbouring Wendat (Huron) and Algonquian peoples; in the many stories of "Indian captives" that sprung up during the Seven Years War (aka the French and Indian War, for those in the States); in the whispered tales of dread at the discovery that the British were enlisting the Iroquois on their side during the American Revolutionary War.

It is the intersecting of the two sides of the coin - the "Noble" and the "Savage" - that reveals the unstable ground upon which European settlers in North America found themselves in trying to define the First Nations around and among them. However, regardless of whether the "Noble" or the "Savage" predominated in popular perception, the conclusion was the same. The settlers believed that the First Nations could not run the show for themselves anymore, but must be guided into a "better" way of life: either more "advanced" (in the case of the "Noble"), or more "civilized/moral" (in the case of the "Savage").

That may be the history, but the story itself does not end here. Stay tuned for the next installment of "Catch-22s in First Nations Depictions" to see how the duality of the "Noble Savage" has become manifest in today's societal views of the First Nations in Canada.

Sources

Bickham, Troy. Savages within the Empire: Representations of American Indians in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print.

Godesky, John. "'The Savages are Truly Noble'". The Anthropik Network, 10 May 2007. Web. 15 June 2014.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques. A Discourse on Inequality. Trans. Maurice Cranston. London: Penguin Books Ltd, 1984. Print.

Image Credits

All historical artworks (c) Their original creators as indicated in the captions, found via Wikimedia Commons