It has been some time since I have last posted here, but I can assure you that I have been hard at work studying, reading, etc. So I hope that this will only benefit and enhance future posts, and I want to thank you for your patience these past several months :)

Recently, the city of Toronto has become a multiculturalism enthusiast's dream with the hosting of the Pan Am Games in July. We have had many tourists from abroad (some of whom I have had the pleasure of interacting with at the Royal Ontario Museum), and there are many ethnic and cultural events scattered around the city for the public to take part in.

Of course, celebrations of ethnic identity are not straightforward: along with the pleasure, there is often pain. We can say we appreciate others' cultures all we want, but with that, we also have to hear people out on the issues and challenges they face, oftentimes because of those identities.

Because of this, I find it interesting that after several months' worth of hiatus, I return to my volunteer post at the Royal Ontario Museum to a number of new exhibits and installations in the Canadian galleries where I work. One of these, Worn: Shaping Black Feminine Identity by Vancouver-based artist Karin Jones, is particularly noteworthy for the ROM initiative it is part of: Of Africa.

Of Africa is a ROM project several years in the making, aimed towards presenting a more diverse image of Africa and its diaspora, dispelling the myth that the African continent is culturally monolithic (i.e. that all Africans can be grouped into a single culture). Also, the use of contemporary modern art will also showcase the vitality of African cultures: they are not trapped in some distant past, but incredibly vibrant and open to creative expression and innovation.

Worn, appearing as it does in the Canadian gallery, is meant to speak about the historical and contemporary reality of African Canadians, working in juxtaposition to the artifacts from European settlement that surround the temporary exhibition space in the rest of the gallery. The art installation is a dress made of synthetic hair in a style evoking the late 19th century bustle dress associated with the Victorian era. In the following pictures, you can see the intricate detailing of the braided hair. In this, we see Jones' argument that African arts (as exemplified through the braiding) are just as beautiful and refined as the European decorative and fashion arts that our society so admires.

You may note that the dress is black. This is not only because of the colour of the synthetic hair, reminiscent of African and Caribbean braids, but because the Victorian dress Jones meant to emulate was a mourning dress. In her own words:

For me, the Victorian mourning dress is a symbol of sadness, "high" culture, the British Empire, and the imposition of feminine beauty norms.

[...]

I wear my African-Canadian identity much as a Victorian woman would have worn this type of dress: proudly, but uncomfortably, shaped and also constrained by it.

Note as well the way the dress is displayed. Cotton balls and hair bolls are scattered upon the floor, testament to the role that Africans have played in the construction of the European empires and the settler colonies that now form today's First World - including Canada.

Canadians may speak of the abolition of slavery and the Underground Railroad that allowed African slaves in the United States to find freedom, but we also cannot forget that we, too, have benefited from the "invisible labour of thousands of Africans": not just in the 19th century at the height of the British Empire, but also into the present day.

Sources

Of Africa. Royal Ontario Museum. n.d. Web. 31 July 2015.

Worn: Shaping Black Feminine Identity. Royal Ontario Museum. n.d. Web. 31 July 2015.

Image Credits

All photos (c) Kita Inoru

Showing posts with label Multiculturalism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Multiculturalism. Show all posts

Friday, 31 July 2015

Tuesday, 2 December 2014

Six Months In: Things I've Learned as a Gallery Interpreter at the Royal Ontario Museum

In terms of my volunteer work at the Royal Ontario Museum, I have recently hit a personal milestone: I have completed my time as what's called a provisional Gallery Interpreter (i.e. a trainee volunteer) and am now officially an active member of the ROM's Department of Museum Volunteers. I do get some perks from this: best one being my own ID badge/key card so I don't need to trouble fellow volunteers to let me in each time I show up for a shift.

So what's a Gallery Interpreter, you ask? What we do is go out into the galleries with a small specimen or artifact that visitors could interact with. Engagements take the form of a short Q&A session, where we use guiding questions to offer information about both the object(s) we have, and the surrounding relevant museum displays. I myself spend most of my time in the two Canadian galleries at the ROM - the Daphne Cockwell Gallery of Canada: First Peoples; and the Sigmund Samuel Gallery of Canada - with one specimen each: a miniature replica birchbark canoe in the first, and a late 19th-century French-Canadian maple sugar mould in the latter.

1. Nothing quite beats working with historical objects.

Especially when said objects just happen to be particularly old, or beautiful, or relevant to your field of interest. I still remember when, in the early stages of my training (i.e. before I was even in the galleries), I was given a demo from an instructor on how one of these Q&A sessions would work. The gentleman had a piece of mosaic with him, and I was to pose as the "visitor". I knew going into the dialogue that the mosaic was used in the ROM's Ancient Roman gallery, but imagine my surprise when I discovered that the fragment I was handling was actually 2,000 years old, and a genuine artifact! And since our initial training included objects from both the ROM's Natural History and World Culture collections, I'm sure that's not even the oldest thing I handled by the time I was done.

2. The fascination applies to visitors as well.

I daresay some of the giddiness that comes from working with historical artifacts might seem to come just from my being somewhat of a history enthusiast. However, it's not just me or fellow museum volunteers and employers who get like that: the visitors do, too. For instance, while the miniature birchbark canoe I work with is a replica, I stand near some First Nations birchbark canoes that are well over a hundred years old. And people love it when I point that out!

The same sort of thing happens with the maple sugar mould as well. Many visitors are fascinated by the fact that not only am I holding an artifact from the late 19th century, but that (with gloves and my supervision) they are welcome to touch it as well. GIs are trained to make sure that artifacts are handled with care at all times (for example: cupping our hands below the visitor's to catch any objects that might fall), so it's a fun and safe experience for everyone involved.

3. Some people just want to be taught.

I've seen this a number of times already in the past six months. The intent for the GIs is to engage with visitors in a conversation, and the Q&A idea stems from that. However, I have had several instances where visitors who are interested don't want the preamble. They'll come right up to me, point at what I'm holding, and ask, "What is that?" Depending on the overall tone of the conversation so far, I sometimes respond by asking for guesses, but it certainly has happened where I end up just telling them directly, and the visitor is very appreciative for the information. This happens a lot with the maple sugar mould in particular, since it's not as immediately recognizable an object as the birchbark canoe. I can see how trying to guess what it is can be rather intimidating, actually.

4. Sometimes, I am the one who gets taught - and that's even better.

Just about every single GI has had an encounter like this: a visitor comes by who turns out to be an expert in the field relating to the object in question. I hear a lot of these stories coming from the Natural History sections of the ROM in particular, especially relating to children who are currently in their dinosaur/animal enthusiast stage.

I myself have had a similar experience with the miniature birchbark canoe. One woman I met turned out, in fact, to be First Nations herself (specifically Ojibway) and made similar miniature canoes as a hobby. So she was the one telling me a lot about the process she used: soaking the birchbark to make it pliable, sewing it with sinew (the ROM's replica uses thread), and even beading her canoes for decoration. That was definitely a rewarding experience, and I hope to have more in the future!

5. Being a GI can be a great chance for cultural exchange.

The ROM receives visitors from all over the world - and even if it didn't, Canada is a sufficiently multicultural nation for us to meet visitors from all sorts of ethnicities and cultural backgrounds. What this means is that some of the conversations I have had as a GI focus around comparisons between cultures: Canadian and the visitor's culture of origin.

Some such instances that come to my mind right now include a Swedish visitor talking about woodworking techniques while looking at the birchbark canoes, an East Asian family comparing the qualities of birchbark as a construction material compared to bamboo, a Brazilian family comparing the handiwork of Canada's First Nations peoples with their own indigenous crafts, yet another Brazilian visitor telling me about how rubber is made from tree sap harvested like Canada's maple sap is, and visitors from maple-producing parts of the United States giving me tips and pointers on some of the inner workings of the business.

And that's just scratching the surface!

6. Sometimes, the visitor's more interested in me than in the objects.

I've had cases where overseas tourists are more interested in sharing to me about their thoughts on their trip to Canada thus far than anything directly related to the objects I'm working with. And that's fine - if everyone is comfortable and at ease, I am more than willing to listen and, hopefully, provide further positive memories for them to bring home.

There's also been one occasion where I was in the First Peoples gallery with the birchbark canoe, and a visitor asked me if I was First Nations myself. I told him that no, I wasn't; I'm actually Chinese. He was surprised, since he thought that if I was working in a First Nations-related gallery, I would likely have to be First Nations myself. That's the sort of question that gave me pause to think for quite a long time afterwards.

7. Because, like it or not, politics does get involved sometimes.

Perhaps this is a lesson that's rather gallery-specific, as I have only had this sort of thing happen to me when I'm in the First Peoples gallery. Many visitors are genuinely curious about the place that the First Peoples have in Canada, and I, being a visible ROM worker, naturally become a magnet for those questions.

This is especially the case since the history of Canada's First Peoples is a painful one: one that is based on what once was a form of cooperation between Native Peoples and Europeans, but that degenerated into oppression and discrimination before now steadily working towards some form of reconciliation and recognition. So it's understandable that some visitors are concerned, for instance, that the ROM is presenting a colonialist view on the history - particularly since so many of our artifacts come from 19th and early 20th century European donors. Other times, however, I am met with surprise that the First Peoples and their cultures have survived through the tribulation into the present day: their view was that this had all been in the past, but the ROM is careful to show the First Peoples in the present as well.

In both cases, I respond the same way: acknowledge the questions and comments, but encourage the visitors to direct them to the actual ROM curators, who could give more thorough answers than me. Particularly in the former case, things can get very touchy, very fast; and as a GI, I'm not in the position to actually discuss the ROM's political stance. So I pass it on, and hope for the best.

I will, however, reveal this much: the First Peoples gallery at the ROM was designed with the input of many First Nations advisers, and the ROM has been careful to make sure that all the current interpretations and commentaries shown are actually from a Native perspective.

Six months in, and I've already learned so much. Who knows where I'll be after another six!

Images

All photographs from the Royal Ontario Museum, taken by Kita Inoru

|

| The ROM's famous Rotunda Ceiling mosaic. The text reads: THAT ALL MEN MAY KNOW HIS WORK |

1. Nothing quite beats working with historical objects.

Especially when said objects just happen to be particularly old, or beautiful, or relevant to your field of interest. I still remember when, in the early stages of my training (i.e. before I was even in the galleries), I was given a demo from an instructor on how one of these Q&A sessions would work. The gentleman had a piece of mosaic with him, and I was to pose as the "visitor". I knew going into the dialogue that the mosaic was used in the ROM's Ancient Roman gallery, but imagine my surprise when I discovered that the fragment I was handling was actually 2,000 years old, and a genuine artifact! And since our initial training included objects from both the ROM's Natural History and World Culture collections, I'm sure that's not even the oldest thing I handled by the time I was done.

2. The fascination applies to visitors as well.

I daresay some of the giddiness that comes from working with historical artifacts might seem to come just from my being somewhat of a history enthusiast. However, it's not just me or fellow museum volunteers and employers who get like that: the visitors do, too. For instance, while the miniature birchbark canoe I work with is a replica, I stand near some First Nations birchbark canoes that are well over a hundred years old. And people love it when I point that out!

|

| One of the original First Nations birchbark canoes at the ROM. I work with a smaller, miniature version when I chat with visitors. |

3. Some people just want to be taught.

I've seen this a number of times already in the past six months. The intent for the GIs is to engage with visitors in a conversation, and the Q&A idea stems from that. However, I have had several instances where visitors who are interested don't want the preamble. They'll come right up to me, point at what I'm holding, and ask, "What is that?" Depending on the overall tone of the conversation so far, I sometimes respond by asking for guesses, but it certainly has happened where I end up just telling them directly, and the visitor is very appreciative for the information. This happens a lot with the maple sugar mould in particular, since it's not as immediately recognizable an object as the birchbark canoe. I can see how trying to guess what it is can be rather intimidating, actually.

|

| 19th-century French-Canadian maple sugar moulds at the ROM. |

4. Sometimes, I am the one who gets taught - and that's even better.

Just about every single GI has had an encounter like this: a visitor comes by who turns out to be an expert in the field relating to the object in question. I hear a lot of these stories coming from the Natural History sections of the ROM in particular, especially relating to children who are currently in their dinosaur/animal enthusiast stage.

I myself have had a similar experience with the miniature birchbark canoe. One woman I met turned out, in fact, to be First Nations herself (specifically Ojibway) and made similar miniature canoes as a hobby. So she was the one telling me a lot about the process she used: soaking the birchbark to make it pliable, sewing it with sinew (the ROM's replica uses thread), and even beading her canoes for decoration. That was definitely a rewarding experience, and I hope to have more in the future!

5. Being a GI can be a great chance for cultural exchange.

|

| Folk musicians from the ROM's Polish Heritage Day in the summer of 2014, one of many such Heritage Days devoted to Canada's many ethnic communities as part of the ROM's summer activities. |

Some such instances that come to my mind right now include a Swedish visitor talking about woodworking techniques while looking at the birchbark canoes, an East Asian family comparing the qualities of birchbark as a construction material compared to bamboo, a Brazilian family comparing the handiwork of Canada's First Nations peoples with their own indigenous crafts, yet another Brazilian visitor telling me about how rubber is made from tree sap harvested like Canada's maple sap is, and visitors from maple-producing parts of the United States giving me tips and pointers on some of the inner workings of the business.

And that's just scratching the surface!

6. Sometimes, the visitor's more interested in me than in the objects.

I've had cases where overseas tourists are more interested in sharing to me about their thoughts on their trip to Canada thus far than anything directly related to the objects I'm working with. And that's fine - if everyone is comfortable and at ease, I am more than willing to listen and, hopefully, provide further positive memories for them to bring home.

There's also been one occasion where I was in the First Peoples gallery with the birchbark canoe, and a visitor asked me if I was First Nations myself. I told him that no, I wasn't; I'm actually Chinese. He was surprised, since he thought that if I was working in a First Nations-related gallery, I would likely have to be First Nations myself. That's the sort of question that gave me pause to think for quite a long time afterwards.

7. Because, like it or not, politics does get involved sometimes.

Perhaps this is a lesson that's rather gallery-specific, as I have only had this sort of thing happen to me when I'm in the First Peoples gallery. Many visitors are genuinely curious about the place that the First Peoples have in Canada, and I, being a visible ROM worker, naturally become a magnet for those questions.

|

| Modern-art sculpture inspired by the traditional Plains First Nations eagle feather headdress: the wapaha. |

In both cases, I respond the same way: acknowledge the questions and comments, but encourage the visitors to direct them to the actual ROM curators, who could give more thorough answers than me. Particularly in the former case, things can get very touchy, very fast; and as a GI, I'm not in the position to actually discuss the ROM's political stance. So I pass it on, and hope for the best.

I will, however, reveal this much: the First Peoples gallery at the ROM was designed with the input of many First Nations advisers, and the ROM has been careful to make sure that all the current interpretations and commentaries shown are actually from a Native perspective.

Six months in, and I've already learned so much. Who knows where I'll be after another six!

Images

All photographs from the Royal Ontario Museum, taken by Kita Inoru

Tuesday, 11 November 2014

The Canadians in Hong Kong: Giving Me My Remembrance Day

|

| WWII Canadian Recruiting Poster referencing Hong Kong |

Sure, in my head, I knew what it was about: every year, November 11 was set aside for Canadians to remember those who had given their lives for the country in WWI, WWII, and subsequent wars since. I'd attend the ceremonies, I'd wear the poppy, I'd recite In Flanders Fields, I'd observe the moment of silence.

But in my heart, I felt nothing.

Perhaps, if you understood where I was coming from, I would not seem so callous. It's not that I didn't appreciate the sacrifices made by our armed forces. I knew what they were fighting for, and supported it as wholeheartedly as the next kid in the classroom. My indifference to Remembrance Day didn't come from some overarching anti-war sentiment. It wasn't anything that noble. No. Little elementary-school-aged me simply thought there was nothing in Remembrance Day to remember. I wasn't born in Canada. My parents weren't born in Canada. I was just a little Chinese immigrant girl from Hong Kong who thought that this was all "white people's stuff".

You could, I suppose, pin some blame on the educational system for this. Because I know now that Canada's military history is, in fact, my military history. Not just because my views have become broader (although they have), but because of something that my school teachers had neglected to tell me: Not only was Hong Kong involved in the World Wars, but Canadians fought there, too.

|

| Troops of C Force en route to Sham Shul Po Barracks, Hong Kong, 16 November 1941. |

And that's when I saw him.

Sounds creepy, yes, but in fact, it was. I've become quite used to seeing models and mannequins in museums by this point, but back then, aged 14, I wasn't. Besides, I was on my own in a museum exhibition about the Canadians in WWII: it was dim, quiet, and just a bit eerie to begin with. The last thing I was expecting to see out of the corner of my eye was the figure of a tall, dirty, Caucasian man, shirtless and clad only in a pair of ragged khaki shorts, standing with his head bowed and his hands stretched out in front, holding a small bowl.

Again, in my head, I must have known that this was simply a model, but that didn't stop me from both being scared out of my wits, and inexorably drawn to him. I knew that I shouldn't be going deeper into the exhibition - I'd get in a good deal of trouble if it was discovered that I was alone, separated from the group and unsupervised. But I did anyway. I wanted to find out who this man was, and why he looked the way he did. After all, I was expecting to see figures of men in uniform, not something so pathetic as this.

And it's at this moment when Remembrance Day for me changed forever. I couldn't bring myself to look at the man directly for very long, but I gleaned enough to discover that he was a representation of the Canadian POWs who had been captured after losing to the Japanese in Hong Kong in December 1941.

|

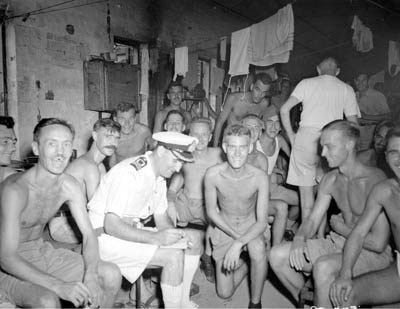

| Canadian and British prisoners-of-war liberated by the boarding party from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, August 1945. |

If anyone here is surprised to find out that either Hong Kong or Canada were involved in the Pacific Theatre in WWII, I don't blame you. That is, after all, what I thought until I was 14. Since then, I've both come to a better understanding of what Canada's forces did all over the world, not just in Hong Kong, and Remembrance Day has become closer to my heart in more ways than one. Perhaps too close, and not always in ways relating to the military, but still: close.

So today, on November 11, 2014, I want to say this to those Canadian soldiers who fought in Hong Kong all those years ago, and their descendents: Thank you. Not only did you do your utmost to defend my land and my people, but you have also helped to shape me into the Canadian that I am today, over 70 years later.

Image Credit

WWII Poster (c) Canadian War Museum

Photographs (c) Library and Archives Canada

Wednesday, 11 June 2014

Celebrating Diversity: Canada during the FIFA World Cup

Chances are, you know that Thursday, June 12, 2014, is the first day of the 2014 FIFA World Cup tournament, which is being hosted by Brazil. I know that for a number of my readers, it'll be a time of anticipation. Soccer (or football, if that's what you call it) is an international sport, and many countries around the world have potential to claim the title of FIFA World Cup champion.

On that note, quick shout-out to those of you who are from countries that have teams playing in the World Cup. I know that there are at least American, Australian, and English readers out there - and quite possibly many more.

I have had a chance to go to England not too long ago, and I could definitely sense the beginnings of World Cup fever. In souvenir stores, jerseys and memorabilia related to the English national team were prominently on display - goods that promoted opposing teams, not so much. And I daresay the same could be said in many other parts of the world right now.

But not Canada.

See, Canada's men's soccer team only ever participated in the FIFA World Cup once: in 1986, and lost every single one of its games. Since then, Canada's tried for entry every single time the World Cup comes around, to no avail: we don't even get past the Qualifiers.

(Note: the WOMEN'S team is another story - Canada has not only participated numerous times there, but does really well for itself!)

So it's not likely, come Thursday and the days following, to see much by way of Canadian flags on cars, fans walking down the street in red-and-white or maple-leaf facepaint, cheering on Canada's teams or its players, etc. The one exception here would be on Canada Day itself, since July 1 does overlap with the tournament. But I digress. The point here is that without a national team or identity to cheer for, Canadians are, in fact, quite free to cheer for whomever they so choose during the FIFA World Cup.

And, boy, do they ever!

I'd show you pictures if I had any. But, I don't. So you'll have to use your imaginations. Just the other day, in a shopping mall parking lot in Toronto, Ontario, I saw a car decorated with an English flag parked right next to one with a Portuguese flag. A week ago, I went out to see a musical downtown, and found a car festooned with Greek flags in the parking lot there. Even among those I know, people are choosing to support different teams: this person says Spain, that person says Brazil, a third person says Argentina. I remember seeing the streets erupt into celebration when Italy won the 2006 FIFA World Cup; and watched the 2010 Final with a Spanish flag in one hand, and a Dutch flag in the other, and loudly cheering for both. And you know what? No one cared that I did.

Growing up in such an ethnically diverse place as the city of Toronto, it's no wonder that even though Canada is not immediately known for its soccer skills (again, with the very important exception of our women's team), there are fans of literally every participating nation in the World Cup just walking the streets here. It's a time of celebration here, where people, just for a moment, revel in the many different peoples and cultures that make up Canada's urban centres. And, on a quick concluding note, now's a really good time for all you Canadians out there to shape up on your flag recognition skills. The next chance won't come around for another four years, it looks like!

References

FIFA, "FIFA World Cup Statistics for Canada". FIFA.com, n.d. Web. 11 June 2014.

On that note, quick shout-out to those of you who are from countries that have teams playing in the World Cup. I know that there are at least American, Australian, and English readers out there - and quite possibly many more.

I have had a chance to go to England not too long ago, and I could definitely sense the beginnings of World Cup fever. In souvenir stores, jerseys and memorabilia related to the English national team were prominently on display - goods that promoted opposing teams, not so much. And I daresay the same could be said in many other parts of the world right now.

But not Canada.

See, Canada's men's soccer team only ever participated in the FIFA World Cup once: in 1986, and lost every single one of its games. Since then, Canada's tried for entry every single time the World Cup comes around, to no avail: we don't even get past the Qualifiers.

(Note: the WOMEN'S team is another story - Canada has not only participated numerous times there, but does really well for itself!)

So it's not likely, come Thursday and the days following, to see much by way of Canadian flags on cars, fans walking down the street in red-and-white or maple-leaf facepaint, cheering on Canada's teams or its players, etc. The one exception here would be on Canada Day itself, since July 1 does overlap with the tournament. But I digress. The point here is that without a national team or identity to cheer for, Canadians are, in fact, quite free to cheer for whomever they so choose during the FIFA World Cup.

And, boy, do they ever!

I'd show you pictures if I had any. But, I don't. So you'll have to use your imaginations. Just the other day, in a shopping mall parking lot in Toronto, Ontario, I saw a car decorated with an English flag parked right next to one with a Portuguese flag. A week ago, I went out to see a musical downtown, and found a car festooned with Greek flags in the parking lot there. Even among those I know, people are choosing to support different teams: this person says Spain, that person says Brazil, a third person says Argentina. I remember seeing the streets erupt into celebration when Italy won the 2006 FIFA World Cup; and watched the 2010 Final with a Spanish flag in one hand, and a Dutch flag in the other, and loudly cheering for both. And you know what? No one cared that I did.

Growing up in such an ethnically diverse place as the city of Toronto, it's no wonder that even though Canada is not immediately known for its soccer skills (again, with the very important exception of our women's team), there are fans of literally every participating nation in the World Cup just walking the streets here. It's a time of celebration here, where people, just for a moment, revel in the many different peoples and cultures that make up Canada's urban centres. And, on a quick concluding note, now's a really good time for all you Canadians out there to shape up on your flag recognition skills. The next chance won't come around for another four years, it looks like!

References

FIFA, "FIFA World Cup Statistics for Canada". FIFA.com, n.d. Web. 11 June 2014.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)