Earlier in this blog, I'd written about how the Canadians fighting in Hong Kong in WWII led to my reaching a greater awareness of Remembrance Day and its significance.

December 7, 1941, is a date that many of my readers would recognize: it was the day that the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, officially launching the United States into WWII. However, this was not a singular attack. Pearl Harbor was part of a co-ordinated series of Japanese military assaults throughout the Pacific Theatre, including the British colony of Hong Kong. Due to time zone differences, the attack on Hong Kong is recorded as having started in the early hours of December 8, 1941; hard fighting for the colony ensued between the Japanese and the defenders (made up of British, Indian, Canadian and native soldiers, at least) until the surrender on December 25, 1941. The surviving Allied soldiers were held as Prisoners of War until the end of WWII in 1945, and the story of these POWs is what often comes to Canadians' minds when they think of Hong Kong at the time.

But my focus here is not on the Canadian soldiers just yet. With all these anniversaries coming around at this time of year, I feel that focusing too strongly on that can stir up old conflicts and resentments towards Japan and its people. Sounds far-fetched? Maybe. But I have seen and heard such comments in person in the past (including claims that Japan deserved the 2011 Tsunami due to the Imperial Japanese Army's actions in WWII) to know not to bring that up. Rather, I want to encourage you, my readers, to step back and look at the Japanese involved in this conflict as people. Who were they, and how did this affect their actions?

Fortunately, my examination of the Canadian role in Hong Kong during WWII has managed to unearth accounts of (at least) two very different cases: one that falls into the common image of Japanese atrocities, and one that completely contradicts it. Both men are still shrouded in mystery, but please allow me to share what I have found thus far.

Kanao Inouye: the "Kamloops Kid"

Kanao Inouye was commonly known as the "Kamloops Kid" due to his being, in fact, a second-generation Japanese-Canadian born in Kamloops, British Columbia. He appears in a number of Canadian POWs' accounts of their imprisonment as an interpreter with a sadistic streak. One interview recalls him giving a POW a severe beating for pointing out poor medical facilities in the camp to a Red Cross worker, while other accounts point at Inouye's taunts, prophesying a Japanese takeover of Canada, and threatening harm to the Canadian POWs' families in that event. After the war, he was identified by POWs in Hong Kong, and was ultimately tried and executed for treason.

Something like this would correlate with many accounts of Japanese atrocities committed during WWII. However, there is more to Kanao Inouye than initially meets the eye, and much of this depth lies upon his being a Canadian citizen at the time. Like the United States, Canada and its government took preemptive measures to prevent traitorous behaviour from its Japanese immigrant population by confining many of them to internment camps well away from the Pacific coast. This is a dark spot on Canadian history, as at the time, Japanese-Canadians had not shown any indication of disloyalty to Canada, and, like their American counterparts, often worked to actively show their loyalty to the Canadian government during this time. So the "Kamloops Kid", then, was an exception instead of an indication of the norm.

So why did he behave this way if he was a Canadian citizen? As it turns out, anti-Asian sentiment was not new to Canada, and Inouye believed himself to have been a victim of bullying during his childhood in Kamloops, British Columbia. Although it was circumstances that led to his being conscripted into the Imperial Japanese Army - he had been studying abroad in Japan there when war broke out - his post near a large group of Canadian POWs prompted a spirit of vengeance. The Canadians in Hong Kong confirm this, noting that Inouye would, in the midst of his harsh treatment of the POWs, make remarks such as, "Now where is your superiority, you dirty scum?"

In other words, Kanao Inouye cannot simply be taken as an example of Japanese soldiers acting cruelly during WWII. His story is also a warning to Canadians and Americans in the present day of the dangerous consequences of racism: in short, racism breeds more racism.

Honda-san: The Mystery Good Samaritan

There is less out there on this man, from what I have seen. I have found several accounts of a Japanese officer and interpreter with the surname Honda who seemed to treat POWs more kindly and humanely than many of his fellows, but, in fact, I do not even know if these accounts point at one man or two. So for our intents and purposes, I will simply call him "Honda-san" ("Mr. Honda" in Japanese).

One account comes from a Canadian officer, Captain S. Martin Banfill, who was captured during a Japanese attack on the Salesian Mission in Hong Kong on December 19, 1941. Prior to the surrender, many POWs were summarily executed, but Banfill was singled out from his men and spared, ending up at a POW camp at the instigation of Honda-san. Had it not been for this, it is likely that Banfill would have died. Attempts to find this mysterious Japanese officer after the war proved futile; a man fitting his description was seen in Nagasaki when the atomic bomb fell on August 9, 1945, but there is no way of knowing if this truly was him or, if so, whether he survived the blast.

A second account comes from Lieutenant C. Douglas Johnston, who was sent to a POW camp after the surrender of December 25. The account of his imprisonment, in full, can be found here. In this, he makes several references to a Sergeant-Major or Warrant Officer, also with the surname Honda, who he describes as "a real gentleman". This was someone who, although known for strict discipline, also engaged with the POWs in conversation and seemed to show genuine interest in them. After the events of the war, Johnston recalls that the Canadian POWs sought to protect him in particular, allowing him to stay at Hong Kong's Peninsula Hotel to keep him safe from any generic reprisals against the Japanese.

Are these two accounts speaking of the same man? It is hard to say based on such little evidence (note that Honda is not an uncommon surname in Japan). But, in my opinion, there is a part of me that would rather these be two different people and two completely separate stories of human decency in the chaos of war. Just like a bad apple could spoil the bunch, particularly good ones can leave behind a very positive impression.

Sources

"C. Douglas Johnston's Story." Hong Kong Veterans Commemorative Association. n.d. Web. 8 Dec 2014.

"Kanao Inouye." Wikipedia. 12 Jan 2014. Web. 8 Dec 2014.

"Remembering the Kamloops Kid." Veteran Affairs Canada. Government of Canada. 19 Nov 2014. Web. 8 Dec 2014.

Roland, Charles G. "Massacre and Rape in Hong Kong: Two Case Studies Involving Medical Personnel and Patients." Journal of Contemporary History. 32.1 (1997): 43-61. Print.

"The Kamloops Kid." WWII in Color. n.d. Web. 8 Dec 2014.

Image Credits

Photo (c) WWII in Color

Showing posts with label World War II. Show all posts

Showing posts with label World War II. Show all posts

Monday, 8 December 2014

Tuesday, 11 November 2014

The Canadians in Hong Kong: Giving Me My Remembrance Day

|

| WWII Canadian Recruiting Poster referencing Hong Kong |

Sure, in my head, I knew what it was about: every year, November 11 was set aside for Canadians to remember those who had given their lives for the country in WWI, WWII, and subsequent wars since. I'd attend the ceremonies, I'd wear the poppy, I'd recite In Flanders Fields, I'd observe the moment of silence.

But in my heart, I felt nothing.

Perhaps, if you understood where I was coming from, I would not seem so callous. It's not that I didn't appreciate the sacrifices made by our armed forces. I knew what they were fighting for, and supported it as wholeheartedly as the next kid in the classroom. My indifference to Remembrance Day didn't come from some overarching anti-war sentiment. It wasn't anything that noble. No. Little elementary-school-aged me simply thought there was nothing in Remembrance Day to remember. I wasn't born in Canada. My parents weren't born in Canada. I was just a little Chinese immigrant girl from Hong Kong who thought that this was all "white people's stuff".

You could, I suppose, pin some blame on the educational system for this. Because I know now that Canada's military history is, in fact, my military history. Not just because my views have become broader (although they have), but because of something that my school teachers had neglected to tell me: Not only was Hong Kong involved in the World Wars, but Canadians fought there, too.

|

| Troops of C Force en route to Sham Shul Po Barracks, Hong Kong, 16 November 1941. |

And that's when I saw him.

Sounds creepy, yes, but in fact, it was. I've become quite used to seeing models and mannequins in museums by this point, but back then, aged 14, I wasn't. Besides, I was on my own in a museum exhibition about the Canadians in WWII: it was dim, quiet, and just a bit eerie to begin with. The last thing I was expecting to see out of the corner of my eye was the figure of a tall, dirty, Caucasian man, shirtless and clad only in a pair of ragged khaki shorts, standing with his head bowed and his hands stretched out in front, holding a small bowl.

Again, in my head, I must have known that this was simply a model, but that didn't stop me from both being scared out of my wits, and inexorably drawn to him. I knew that I shouldn't be going deeper into the exhibition - I'd get in a good deal of trouble if it was discovered that I was alone, separated from the group and unsupervised. But I did anyway. I wanted to find out who this man was, and why he looked the way he did. After all, I was expecting to see figures of men in uniform, not something so pathetic as this.

And it's at this moment when Remembrance Day for me changed forever. I couldn't bring myself to look at the man directly for very long, but I gleaned enough to discover that he was a representation of the Canadian POWs who had been captured after losing to the Japanese in Hong Kong in December 1941.

|

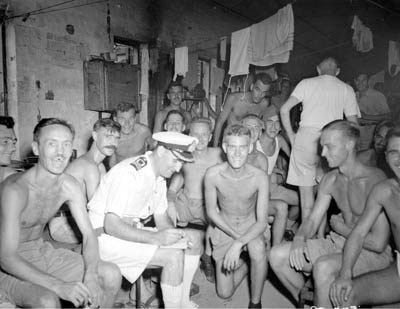

| Canadian and British prisoners-of-war liberated by the boarding party from HMCS Prince Robert, Hong Kong, August 1945. |

If anyone here is surprised to find out that either Hong Kong or Canada were involved in the Pacific Theatre in WWII, I don't blame you. That is, after all, what I thought until I was 14. Since then, I've both come to a better understanding of what Canada's forces did all over the world, not just in Hong Kong, and Remembrance Day has become closer to my heart in more ways than one. Perhaps too close, and not always in ways relating to the military, but still: close.

So today, on November 11, 2014, I want to say this to those Canadian soldiers who fought in Hong Kong all those years ago, and their descendents: Thank you. Not only did you do your utmost to defend my land and my people, but you have also helped to shape me into the Canadian that I am today, over 70 years later.

Image Credit

WWII Poster (c) Canadian War Museum

Photographs (c) Library and Archives Canada

Friday, 6 June 2014

Juno Beach: Canada's Pride of World War II

Today, on June 6, 2014, there are people all across the world who are stopping to reflect upon D-Day and the assault on Normandy. Seventy years ago today, a joint British, American, and Canadian force worked to push back the German forces that were posted on the beaches of Normandy, in northwestern France. Their success that day is now remembered as a significant turning point in the War: the opening of a western front from which point the Allies could force the Germans back to their own borders. It's an event that's so well known that it has been immortalized in song and film several times ever since.

That's a rather older example, and not all that familiar to those in my generation, I daresay. But what about this one?

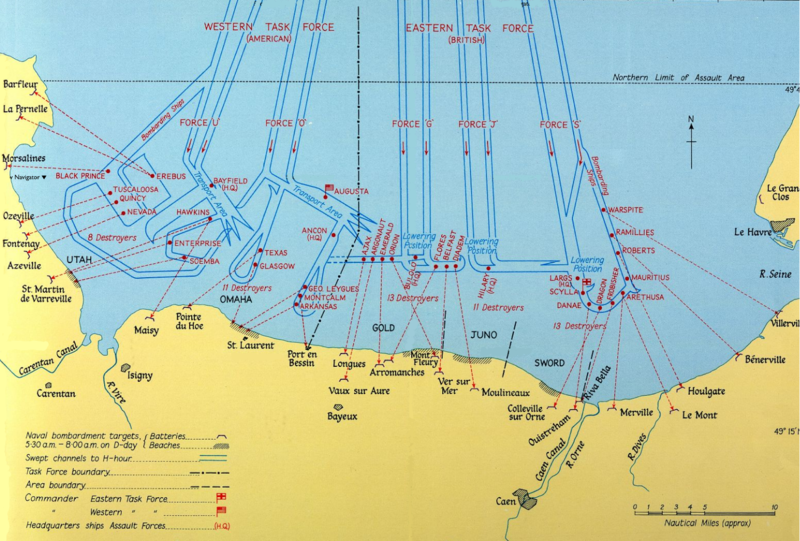

The point is that D-Day has become associated with two things, primarily: Allied determination, and extreme bloodshed. Doubtless it was a bloody, hard-fought battle: just the immense scale of the operation should give that away. Five beaches were attacked by the Allies on June 6, 1944. From west to east, these beaches were code-named Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

Hollywood, being what it is, has tended to focus on the two beaches that were tasked to the American forces: Utah and Omaha (it is the latter that is shown in the opening scenes of Saving Private Ryan, for instance). The British were focused on Gold and Sword. That left Juno to the Canadians - and it has been a great source of national pride ever since.

Canada was heavily involved in the fighting during both WWI and WWII. As a nation and military force, Canada does not hold the same level of prestige as Britain, the United States, France, Germany, etc. In both cases, it is because the Canadian efforts have been seen as joint efforts with others. In WWI, Canada was a dominion of the British Empire, and did not even hold sufficient right to declare war on its own: once Britain was in, Canada was in, no ifs, ands, or buts about it. As for WWII, although Canada had attained enough international clout to issue its own declaration of war and handle its own international affairs, it was still popularly conceived as "British".

What this means is that like the other Commonwealth nations (ex. Australia and New Zealand), Canadians have taken particular responsibility in remembering their own achievements from WWI and WWII. For Canadians, then, we then sought out instances where our soldiers have gone above and beyond the call of duty to create something significant not just to our own history, but to the wars' progression overall. In WWI, that lot fell to Vimy Ridge (April 9-12, 2917); and in WWII, although the credit could be more diversely distributed, most of the emphasis has fallen upon Juno Beach.

Why Juno Beach? Because there was, in fact, a Canadian distinction involved. It's something that many Canadian schoolchildren know, and it's reiterated year after year on Remembrance Day (November 11) and also on the anniversary of D-Day itself: the Canadian troops were the first to reach their assigned goal out of all the Allied divisions involved, and - because of that - were able to penetrate further into German-occupied France than any of the others on that day.

Now, I'm not a military historian. I can't tell you the hows of Canada's victory at Juno Beach, or why the Canadians were the first to achieve success. There are plenty of books, websites, etc. addressing that issue, I reckon. All I want to do is give the Canadian troops that took part in D-Day their proper recognition. Hollywood might give us the American story, but D-Day was a joint effort - without each force involved doing its part, the offensive as a whole may not have succeeded.

And I think, for Canada, seventy years later, that's what matters most.

Image Credits

Screenshot from The Longest Day (c) 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from Saving Private Ryan (c) Amblin Entertainment

Map of Normandy Beaches (c) HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office) and the National Archives (UK)

All photos of Canadian forces in 1944 (c) Library and Archives Canada

|

| John Wayne in the 1962 film The Longest Day |

|

| Screenshot of the Normandy landing from Saving Private Ryan. |

Canada was heavily involved in the fighting during both WWI and WWII. As a nation and military force, Canada does not hold the same level of prestige as Britain, the United States, France, Germany, etc. In both cases, it is because the Canadian efforts have been seen as joint efforts with others. In WWI, Canada was a dominion of the British Empire, and did not even hold sufficient right to declare war on its own: once Britain was in, Canada was in, no ifs, ands, or buts about it. As for WWII, although Canada had attained enough international clout to issue its own declaration of war and handle its own international affairs, it was still popularly conceived as "British".

What this means is that like the other Commonwealth nations (ex. Australia and New Zealand), Canadians have taken particular responsibility in remembering their own achievements from WWI and WWII. For Canadians, then, we then sought out instances where our soldiers have gone above and beyond the call of duty to create something significant not just to our own history, but to the wars' progression overall. In WWI, that lot fell to Vimy Ridge (April 9-12, 2917); and in WWII, although the credit could be more diversely distributed, most of the emphasis has fallen upon Juno Beach.

|

|

Infantrymen of The Highland Light Infantry of Canada

aboard LCI(L) 306 of the 2nd Canadian (262nd RN) Flotilla en route to

France on D-Day, 6 June 1944. (Photograph by Lieut. Gilbert Alexander Milne)

|

Now, I'm not a military historian. I can't tell you the hows of Canada's victory at Juno Beach, or why the Canadians were the first to achieve success. There are plenty of books, websites, etc. addressing that issue, I reckon. All I want to do is give the Canadian troops that took part in D-Day their proper recognition. Hollywood might give us the American story, but D-Day was a joint effort - without each force involved doing its part, the offensive as a whole may not have succeeded.

And I think, for Canada, seventy years later, that's what matters most.

|

|

Three "D-Day originals" of the Regina Rifle Regiment

who landed in France on 6 June 1944. Ghent, Belgium, 8 November 1944. (Photograph by Lieut. Donald I. Grant)

|

|

| Private C.L. Jewell of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders, who wears a "D-Day" beard, Normandy, France, 22 June 1944. (Photograph by Lieut. Ken Bell) |

Image Credits

Screenshot from The Longest Day (c) 20th Century Fox

Screenshot from Saving Private Ryan (c) Amblin Entertainment

Map of Normandy Beaches (c) HMSO (Her Majesty's Stationary Office) and the National Archives (UK)

All photos of Canadian forces in 1944 (c) Library and Archives Canada

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)